Text of my ‘When Worlds Collide’ column published in Ceylon Today Sunday newspaper on 1 April 2012

Few among us have personal memories of the Japanese air raid of Ceylon that happened on the Easter Sunday, 5 April 1942.

Yet the event’s 70th anniversary, falling this week, is a good occasion to reflect on how timely gathering and sharing of information can change the course of history. Although technology has advanced by leaps and bounds since, fundamental lessons can still be learnt.

The Colombo air raid took place exactly 119 days after the Pearl Harbour attack. In that time, the Japanese military had advanced westwards in the Indian Ocean with astonishing speed and success.

When Singapore fell in February 1942, it was widely believed that the next Japanese target was Ceylon. Once their battleships, aircraft carriers and submarines were based in Ceylon, their domination over the Indian Ocean would be consolidated.

If the Allies read Japanese intentions correctly, they completely underestimated their adversary’s capabilities. Lack – or deliberate blocking – of information had characterised the build up of Japanese military capabilities for years.

Their Zero fighter planes proved one of the greatest surprises. Developed by the Imperial Royal Navy Air Service and deployed from early 1939, it was the most versatile carrier-based fighter in the world, combining excellent maneuverability, high firepower and a very long flying range. The Zeros played a key role in the Battle of Ceylon.

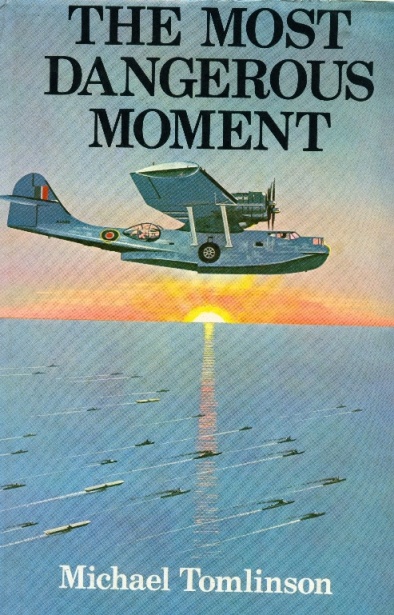

Michael Tomlinson, an Englishman who was posted in Ceylon with the Royal Air Force in 1942, later wrote the definitive book about those fateful weeks. Its title, The Most Dangerous Moment, was derived from a remark by British Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill.Looking back later, Churchill said the most dangerous moment of the Second World War, and the moment that caused him the most alarm, was when the formidable Japanese fleet was approaching Ceylon.

In anticipation, Ceylon’s newly appointed Commander in Chief, Admiral Sir Geoffrey Layton, and Civil Defence Commissioner Sir Oliver Goonetilleke initiated preparations and precautions. These included building several new airstrips, and placing RAF squadrons on the island.

Operating from the Koggala lagoon, Allied airmen conducted aerial patrols of the Indian Ocean using long-range Catalina aircraft – multipurpose ‘flying boats’. With no satellites, and radar still in its infancy, these ‘eyes in the air’ offered crucial surveillance.

On the evening of 4 April 1942, just before dusk, one such Catalina made a chance observation that changed the course of history. As they were about to turn back, Leonard Birchall, a young Squadron Leader of the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), saw a ‘black speck’ in the Indian Ocean. Upon investigation, they discovered a Japanese aircraft carrier fleet, at the time 400 miles (640km) south of the island.

As the Catalina’s crew took a closer look, its radio operator radioed to Colombo the location, composition, course and estimated speed of the advancing fleet. Moments later, they were shot down by Zero fighters: Birchall and crew mates spent the rest of the War as Japanese prisoners.

The message reached Colombo “a little garbled but essential correct” and immediately passed on to all the Services. But what happened thereafter shows that an early warning by itself serves little purpose unless it is properly acted upon.

The next day, 5 April, was Easter Sunday. The authorities decided not to issue any public warning about the impending air raids, “lest it precipitate a possible panic” says Tomlinson.

In the event, the air raid caught Colombo’s defenders almost by surprise.

The Catalina’s radio message wasn’t the only warning. As Tomlinson records: “The huge air armada had made its landfall at 7.15 in the Galle area and flew up on the coast for half an hour at a height of some 8,000 feet. Thousands must have seen and heard them. Whether radar picked them up or not was scarcely material for the Hurricanes [British fighter aircraft] could have been given half an hour’s adequate warning with merely visual aids.”

Even worse, an RAF crew going out on a Catalina patrol that morning had seen the advancing Japanese planes flying far above them – yet, assuming them to be friendly, didn’t break radio silence to report it!

How and why these obvious clues were missed has never been satisfactorily explained.

Ceylon had only basic radar facilities at the time. Apparently radar was unmanned at the crucial moment when watchers were being changed. And at 7.30 am, when a dawn attack didn’t materialise as expected, some airmen at Ratmalana Airport were released for breakfast.Twenty minutes later, Japanese formations appeared overhead. Many of RAF’s Hawker Hurricanes were still on the ground, and proved sitting ducks. Others scrambled to take off. The ensuing defence was hurried, scattered – and needlessly costly.

“Failure in communications all around was to bring tragic results in its wake,” says Tomlinson. “Afterwards, there was even talk about sabotage, but this cannot be taken seriously.”

It was also a failure of imagination and intelligence gathering. No one knew the Japanese aircraft had such long range; it was assumed that their carriers had to get much closer to the island before the planes could take off.

The Easter Sunday Raid, or the Battle of Ceylon, is well documented. Much to the surprise and disappointment of the Japanese, the Allied naval fleet had been moved out of the Colombo habour. Another Pearl Harbour was thus avoided.

The Colombo air raid lasted some 20 minutes, and the civilian casualties amounted to 85 dead and 77 injured. The British claimed destroying “27 enemy aircraft” that morning, but the Japanese admitted losing only five. Tomlinson speculates that some damaged aircraft never managed the long flight back.

On April 9, the Japanese bombed Trincomalee harbour and attacked British ships off Batticaloa. Close to a thousand Allied servicemen lost their lives defending Ceylon that week. The Japanese never returned.

Leonard Birchall survived the notorious Japanese prison camps. Decorated and hailed as the ‘Saviour of Ceylon’, he died in September 2004 aged 89.

Three months later, the Boxing Day Tsunami would head to the island at the speed of a modern jetliner. An early warning from Hawaii would go unheeded in Colombo – and up to 40,000 perish within a few hours.

But that, as they say, is another story.

Sri Lanka Air Force website page on Battle of Ceylon

Follow me on my blog: http://nalakagunawardene.com, and on Twitter: NalakaG

Reblogged this on Moving Images, Moving People!.

Thanks a lot Nalaka for writing this. Never read such a comprehensive account on this saga.