Text of my ‘When Worlds Collide’ column published in Ceylon Today newspaper on 5 September 2014

Small island nations are in focus this week, as well as throughout this year.

The Third International Conference on Small Island Developing States (SIDS) was held from 1 to 4 September 2014 in Apia, Samoa, in the Pacific. Its theme was “sustainable development of SIDS through genuine and durable partnerships“.

The United Nations, convener of the conference, has also designated 2014 as the International Year of Small Island Developing States (details at: www.sids2014.org). The year is meant to express global solidarity with the small island states around the world.

SIDS was first recognised as a distinctive group around the time of the first Earth Summit in 1992. They are low-lying coastal countries sharing many development challenges, including small populations, limited natural resources, remoteness, susceptibility to disasters and fragile environments. Many are on the frontline of climate change impacts.

The UN currently lists 51 SIDS. Of them, just four are in the Indian Ocean: Maldives, Mauritius, Seychelles and Singapore (most are in the Pacific and the Caribbean). The only one in South Asia, the Maldives, has long been vocal on the high vulnerability of such states.

The Maldives is the smallest country in Asia in both population and land area: it packs around 350,000 people into just under 300 square km. Located south-west of India and Sri Lanka, it is an archipelago of 1,192 islands, of which only 200 are inhabited.

With an average ground level of 1.5 metres (5 feet) above sea level, it is also the lowest country on the planet.

In a new report, the Asian Development Bank recently cautioned that the Maldives could be the hardest hit economically from climate impacts: it could cause annual economic losses of over 12% of GDP by the end of this century. The report, titled ‘Assessing the Costs of Climate Change and Adaptation in South Asia’, came out in June 2014.

Sea Level Rise

An expected rise of 2 degrees Centigrade in the world’s average temperatures during this century – due to human-made global warming — could seriously affect island states like the Maldives. They are least able to cope with extreme weather events and rising sea levels.

In a 2013 report titled Turn Down The Heat: Climate Extremes, Regional Impacts, and the Case for Resilience, the World Bank envisaged sea levels rising in South Asia by 60 to 80 cm if temperatures rise by 2 degrees C by 2100, relative to 1986-2005.

As the planet warms, melting polar ice caps and glaciers increase the volume of sea water. Warmer waters also expand, taking more space. According to the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), the global sea level has already risen by about 10 to 25 cm (up to about 10 inches) during the last 100 years.

Sea level rise is a gradual process, not a single event like a tsunami. First, land gets flooded temporarily during high tide or stormy weather. Salt intrusion can render soil and groundwater unusable well before permanent inundation happens.

The Maldivians saw early signs of this in April 1987, when the highest tidal waves in living memory flooded a third of the capital Malé during a storm. It washed away reclaimed land and caused widespread property damage.

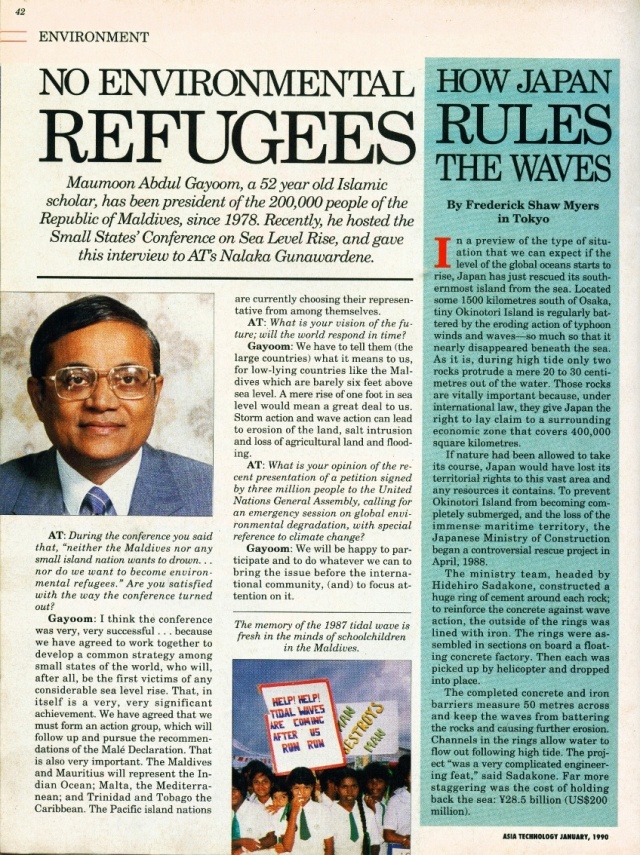

Later that year, then President Maumoon Abdul Gayoom raised the issue at the UN General Assembly, and appealed for help to nations like his. His was among the first such voices, at a time when climate change was just beginning to gain international attention.

In 1989, Gayoom followed up by convening the first small states conference on sea level rise. It brought together representatives from most such nations, along with climate researchers and international organisations. It was the beginning of joint advocacy that was later picked up by the Alliance of Small Island States, AOSIS, formed in 1990.

My own climate related reporting was enhanced by covering that event. In an interview at the time, President Gayoom said: “A mere rise of one foot in sea level would mean a great deal to us. Storm action and wave action can lead to erosion of the land, salt intrusion and loss of agricultural land, and flooding.”

Asia Technology magazine – Jan 1990 – Nalaka Gunawardene interview with President Maumoon Abdul Gayoom

His successor President Mohamed Nasheed, who took over in late 2008, called the plight of his people a human rights issue and also a threat to national security. In a clever communications move, he held a cabinet meeting underwater in October 2009 to illustrate what could unfold in a few decades.

Carbon Neutral Plan

He announced in 2009 that the whole country would become carbon neutral in a decade. The plan involved phasing out fossil fuel use with renewable sources (solar, wind and biomass), improving energy efficiency, and an integrated solid waste management system.

“We understand that our becoming carbon-neutral will not save the world, but at least we would have the comfort of knowing that we did the right thing,” President Nasheed said at the time.

Nasheed also saw good governance as an essential component of climate adaptation. He told me in an interview in 2009: “Traditionally, we’ve always thought that adaptation represents physical structures –revetments, embankments, breakwaters, etc. But the most important adaptation issue is good governance and, therefore, consolidating democracy is very important for adaptation.”

Watch short film based on my 2009 interview with President Nasheed:

Political storm

That vision has run into some recent turbulence. After President Nasheed resigned in February 2012, the Maldives experienced considerable political unrest. Preoccupied with uncertainties of the present, Maldivians have not had much time to reflect on their long term survival.

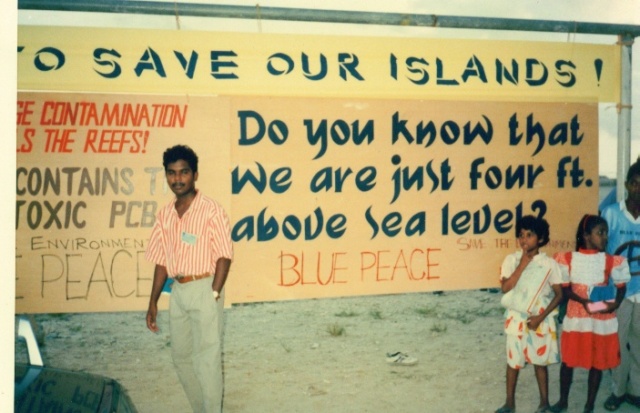

Ali Rilwan, Executive Director of Bluepeace, the counry’s oldest environmental organisation, told me in June this year that his group was unclear where plans for carbon neutrality stand.

“Even (the current) President Yameen’s government has not mentioned a word about Maldives (going) carbon neutral by 2020,” he said.

The current government has, however, endorsed a low carbon development strategy to improve energy security. In May 2014, Minister of Environment and Energy pledged to ‘minimize the country’s dependence on fossil fuels’ and called for increased investment in clean energy. The government wants to generate 30% of the daily peak electricity demand from renewable sources.

Ali Rilwan of Bluepeace Maldives during Small Island Conference on Sea Level Rise, Nov 1989 – Photo by Nalaka Gunawardene

Adaptation strategies

With their contribution of global warming gases miniscule by global standards, the priority for most SIDS is how to brace themselves for inevitable climate impacts. Adaptation is the only way for Maldivians to ensure their islands remain habitable.

Healthier ecosystems will be more resilient against adverse impacts, giving islanders more time to take other measures. Bluepeace recommends ecosystem-based adaptation for the short and medium term. That means conserving land, freshwater and marine ecosystems as well as restoring those already degraded.

A particular concern is the health of coral reefs on which the nation’s key economic activity of tourism depends. Coral reefs are the first line of defence against wave action and storm surges. The warming seas triggered large scale coral bleaching in 1998 and 2010, causing much damage. Healthier reefs can recover faster.

“It is imperative to protect the coral reefs, sea grass, coastal vegetation and wetlands to mitigate the adverse impacts of climate change,” says Rilwan.

For the longer term, elevating entire islands is an option, albeit a very expensive one. Hulhumalé, a reclaimed island inaugurated in 2004 to ease congestion on the capital, has an elevation of 2 metres above sea level.

Can the Maldivians adapt fast enough to outpace the rising seas? Only time will tell.

Coral bleaching 2010, Maniyafushi, 0ver 50% corals bleached but recovered causing little mortality – Photo by Bluepeace, Maldives

Follow me on my blog: http://nalakagunawardene.com, and on Twitter: NalakaG